LAST NEWS

An interview with Manuel Romero. "Guerrilla marketing disseminates the advertiser's message through surprising and unlimited means."

- How did you learn ‘guerrilla marketing’?

- I'm a journalist. I didn't intend to devote myself to advertising or marketing, but personal and professional circumstances left me with a football at my feet and I took a shot. I took aim at the goal and it turned out that I showed some ability for guerrilla marketing. In the meantime I crossed paths with several advertisers who I was able to inspire with my passion for getting their messages and products across through new ways of advertising. It was a period when traditional media was languishing. At the same time, television was expanding with new platforms and an infinite number of channels. The Internet, cell phones and other mobile devices have transformed the individual into a self-sufficient communications unit. It's gotten to the point where every person has become a global receiver and transmitter through the use of social networks. Any individual has the ability and possibility to reach the other side of the world in a matter of seconds with their messages of affinity, support or criticism. At this level, guerilla marketing offers extraordinary possibilities. It's the advertising method which best conforms to the new social and technological situation.

- Did your professional experience as a journalist serve your activities in the world of marketing?

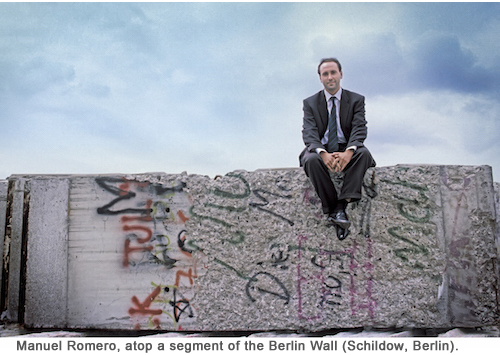

- It's not just that it was useful; without my experience as a journalist it would have been impossible to develop my activities in guerrilla marketing. You have to be up to date with current events, trends and the opinions of people responsible for moving and changing the world. These can be heads of state, like Gorbachev, who put an end to the USSR; lawyers like Jules Rimet, who created the FIFA; or anonymous unknown figures like the German citizen who grabbed a pickaxe and began to raze the Berlin Wall the night it fell, becoming an icon beyond the current moment.

- What does guerrilla marketing offer that traditional advertising doesn't?

Guerrilla marketing disseminates the advertiser's message in surprising, unusual and unique ways… Society has become accustomed to overly-used advertising schemes, so worn out and hackneyed that now they rarely penetrate very deeply, unless they have an enormous enough budget to invade the media by air, land and sea: TV ads, radio spots, press insertions, digital banners… But how do you reach the public in a more selective fashion, with more credibility and depth? Guerrilla marketing possesses these tools: imagination in the form, so that the content, that is, the message, can reach its audience in a more effective and attractive manner. That's why it's called 'guerrilla': a surprise attack and an assault with a very specific objective. It's not necessary to use massive, general means to invade society through advertising; instead, you use selective resources and novel channels to reach very specific and attuned groups with the messages aimed at them.

Guerrilla marketing disseminates the advertiser's message in surprising, unusual and unique ways… Society has become accustomed to overly-used advertising schemes, so worn out and hackneyed that now they rarely penetrate very deeply, unless they have an enormous enough budget to invade the media by air, land and sea: TV ads, radio spots, press insertions, digital banners… But how do you reach the public in a more selective fashion, with more credibility and depth? Guerrilla marketing possesses these tools: imagination in the form, so that the content, that is, the message, can reach its audience in a more effective and attractive manner. That's why it's called 'guerrilla': a surprise attack and an assault with a very specific objective. It's not necessary to use massive, general means to invade society through advertising; instead, you use selective resources and novel channels to reach very specific and attuned groups with the messages aimed at them.

- You began this new profession coinciding with the transformation that Europe underwent following the collapse of the communist block and the Iron Curtain.

- It so happens that as a child I grew up in Germany, at the time a divided country. So I was witness to the trauma that the Wall provoked in German society as well as the political maneuvers that each government in Bonn made in their attempts to resolve the partition, their search for coexistence and a future of freedom for both sides… a very distant prospect, given that periodically someone died attempting to escape from the GDR. It was an open wound in the heart of Europe. At the end of the 80s, the collapse of the fictional communist paradise occurred and I was fascinated by a world in which one day a border fell, the next day others were erected and during the weekend a head of state was toppled and executed. All this in a Europe that until then we thought was on the sidelines of the world's turmoil. We though the changes would be slow, without traumas, uprisings or wars. Finding myself in Budapest on November 9, 1989, the day the Berlin Wall was to fall, was vital. As a journalist, I was covering the visit of Spanish president Felipe González to Hungary, and during an informal meeting with the Spanish press late that afternoon of November 9th, I asked him how long he thought it would take for the Wall to disappear, after a summer which had seen the mass exodus of East Germans by way of other Eastern Bloc countries. He responded that we were faced with a lengthy process and that it would take years before that goal was reached. At the very same hour that Felipe González was answering my question, Gunter Schabowski, spokesman for the GDR's government, was holding a press conference in East Berlin and added, at the end of a confused and muddled statement, with no apparent conviction, that East Germans could travel freely to the Federal Republic "with immediate effect," uttered without emphasis. This provoked an avalanche of thousands of people before Berlin's border crossings in the early morning hours. At dawn the next morning, while it was still dark outside, I awoke in Budapest to the news. I abandoned the press corps accompanying Felipe González, boarded an Interflug flight to East Berlin and joined the multitude that was crossing from East to West through Checkpoint Charlie; tens, probably hundreds of thousands of people who had no idea what exactly awaited them on the other side, though they knew in general terms what Freedom was. Only months before, Erich Honecker, the man who had organized the construction of the Wall in 1961 and who had been president of the GDR until October, 1989, had arrogantly proclaimed that that inhuman barrier dividing Germany would last another 50 or 100 years. In November, 1989, the Wall fell and many things changed. Three months later I launched Innova y Comunica Media as a response to the new demands of advertising whose fast approach could be intuited, coinciding with the birth of private television stations in Europe. In the spring of 1990, I took my first steps in the world of publicity, employing the new commercial formats integrated into German TV game shows, and by summer I was buying 8 segments of the Berlin Wall, weighing a total of 20,000 kilos, which would help three clients achieve notoriety: Tribuna magazine, for offering pieces of the Wall to its readers and promote sales; Madrid's City Hall for placing them in the capital's Parque de Berlin as a monument to Freedom; and Autopistas de Navarra to highlight the message of Peace near the border with the Basque Country.

That is how you began the task of demystifying Eastern Europe as a launching pad for your clients' advertising with guerrilla marketing techniques.

That's right. After the Berlin Wall came Moscow's Red Square, where in 1992 I hung the first billboard, which served as sponsor for the first large civic celebration of May Day, without the official parade of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The advertiser was the Canary Islands Tourist Office. Then came the installation of an enormous advertising banner which covered 600 meters of China's Great Wall; and later the journey of a deactivated Soviet Scud missile which I transported across the whole of Europe, from Moscow to Algeciras, from whence it was carried by ship to the island of Lanzarote. In a Europe frightened of itself and of what was happening beyond the continent, the Canary Islands brand acquired widespread notoriety as a tourist destination. At the beginning of the 90s, Saddam Hussein had invaded Kuwait and had provoked the first Gulf War and its sequels, which lasted several years. By contrast, a place like the Canary Islands carried with it no risks, and its image, combined with impact advertising, was very effective.

- You had been in Iraq at the end of the 80s.

That's right, during the war with Iran. I was 27. At first I was in Bagdad, where the suffering and signs of war evaporated at night with festive celebrations of Ramadan, while the caskets of those who had died at the front were taken home to their families on the roofs of the taxis. It was forbidden to do so during the day to avoid the population witnessing this somber scene amidst the traffic, and so becoming demoralized. The city was apparently peaceful; I went everywhere in the city without protection, and the kids playing football on the sidewalks asked you if you were fans of Real Madrid or Barça. Basra, on the other hand, where I went next, was a ghost city, destroyed by the conflict with Iran. It was impossible to walk in the streets because the bombs and missiles had fallen all over and there were craters everywhere. All the buildings were protected by sandbags and there was the barrel of a gun behind every corner. At night it was impossible to sleep from the roar of missiles and at dawn a body count was made of those killed by the enemy during the night. It was there that I learned to distinguish the blast of a battery of Katiuskas from the impact of a Scud. What I am trying to say is that when I was in Moscow five years later and I was shown an armaments catalogue to choose which one would be destined for the Monument to Peace in Lanzarote, the landscape of death and destruction that they left in the wake of their explosions was not unknown to me. And, just as before buying a missile I was already familiar with its roar, before acquiring the segments of the Berlin Wall I had already climbed it and jumped to the other side.

That's right, during the war with Iran. I was 27. At first I was in Bagdad, where the suffering and signs of war evaporated at night with festive celebrations of Ramadan, while the caskets of those who had died at the front were taken home to their families on the roofs of the taxis. It was forbidden to do so during the day to avoid the population witnessing this somber scene amidst the traffic, and so becoming demoralized. The city was apparently peaceful; I went everywhere in the city without protection, and the kids playing football on the sidewalks asked you if you were fans of Real Madrid or Barça. Basra, on the other hand, where I went next, was a ghost city, destroyed by the conflict with Iran. It was impossible to walk in the streets because the bombs and missiles had fallen all over and there were craters everywhere. All the buildings were protected by sandbags and there was the barrel of a gun behind every corner. At night it was impossible to sleep from the roar of missiles and at dawn a body count was made of those killed by the enemy during the night. It was there that I learned to distinguish the blast of a battery of Katiuskas from the impact of a Scud. What I am trying to say is that when I was in Moscow five years later and I was shown an armaments catalogue to choose which one would be destined for the Monument to Peace in Lanzarote, the landscape of death and destruction that they left in the wake of their explosions was not unknown to me. And, just as before buying a missile I was already familiar with its roar, before acquiring the segments of the Berlin Wall I had already climbed it and jumped to the other side.

- Is it difficult to convince the authorities of the countries where you undertake guerrilla actions?

I've had various experiences. I negotiated the placement of the first advertisement in Moscow's Red Square in a single weekend, by phone and fax, after proposing the idea to the client six months earlier. That I knew Igor Makurin, then director of new projects for Itar-Tass, the Russian news agency, was crucial; he had been a correspondent in New York and had returned to Moscow to try to save the coffers of the state information agency. Itar-Tass took care of organizing that May Day in Red Square and to line up sponsors, but no commercial brand dared do so. On Saturday, April 25th I learned that they needed financing for the civil celebration and I called the Canary Islands and told them that we could get advertising space in front of Lenin's Tomb, and they gave me the green light. The agreement was concluded the next day and I sent the design in by fax so the Bolshoi Theater's art department could get it down on a piece of fabric that covered 64 meters square of the GUM department store's façade in the heart of the square where portraits of Lenin or Stalin had always been hung every May Day. By contrast, the negotiations and organization for the advertising banner on the Great Wall took me two years, from the acceptance of the idea to its execution, with various trips to China in order to convince my counterparts, the Beijing Tourist Office, that the banners should have a white background, not a red one, which is what they were demanding. In the case of the agreement for purchasing the Scud missile, I did it, catalogue in hand, in the lobby of the Ministry of Defense of the CIS, the Commonwealth of Independent States, as the disintegrating Soviet Union was temporarily designated. But the details of transporting the missile on a truck by highway required six months of negotiations with the transport company, not to mention the German customs authorities. I lived through dozens of the most bizarre situations in the solitude of the Russian autumn, which is the equivalent of our harshest winter. In the end, despite the spectacular military send-off that Moscow's City Hall and the Russian army organized in the center of the city, the truck carrying the missile was only able to leave Moscow customs thanks to a crate of whiskey.

- And that's how you opened a new route that others after you have traveled.

- Eastern Europe offered us this opportunity. What I actually offered was brand notoriety through unusual and unique actions, implemented from the conception of the idea to dissemination and the final repercussions. Other companies and institutions opted to turn to my agency in order to employ this formula, which is inexhaustible but exhausting for those carrying it out. It requires imagination, being up to day with information, with relationships, with trends and social and technological movements. Each case of guerrilla marketing is a world unto itself and is rarely repeated. An enormous degree of honesty must accompany the creativity so as to not simply offer notoriety for notoriety's sake, but in order to revitalize and increase the product's consumption.

Do you think there are any limits to guerrilla marketing?

In the sphere of ethics, undoubtedly. Generating notoriety is relatively simple, but doing it with a commercial sense in order to reach a goal is much more difficult and requires professionalism and techniques for evaluation the impacts. In the technical sphere, guerrilla marketing has no limits. With each step humanity takes, a new possibility arises for incorporating messages with a commercial end. Each new change or trend in the world opens a new and subtle window for advertising, which coexists with the event, and moreover, can complete and even enrich the historic event. Otherwise, what better end could there be for the Berlin Wall or the elimination of nuclear arms than for their conversion by sponsors into monuments to Peace and Freedom in some corner of the world? And why not invite a cosmonaut who has been enclosed in a space station for 747 days and orbiting the Earth 11,968 times but who has never enjoyed a warm beach here below, to spend his vacation on an island paradise? This is why, in the Gold Book of Guerrilla Marketing, each chapter opens with a historic figure who inspires the guerrilla marketing action described immediately after. I not only illustrate a piece of advertising, but the historical and social context that preceded it.

Do you think that guerrilla marketing solutions are inexhaustible?

- Absolutely. Human beings will always use their imaginations to present messages in an original fashion and increase their effect based on the curiosity and permeability shown by their fellow man.

Why did you decide to publish the Gold Book of Guerrilla Marketing?

- For a personal need to register important years of my life, so that my two sons and my daughter would know what Dad was doing when they were kids and always arrived home late or wasn't always there on Sunday; when I flew to Moscow, I stayed two days, then I went to Beijing and returned home just in time for a birthday. In this aspect, my wife was my greatest support. Naturally, I also created the book for professional reasons. Among the conditions required for the activity of guerrilla marketing is that of discretion: I've always remained behind the scenes, out of the spotlight. The 27 cases I describe in the book form part of a very specific historical period that can be considered concluded, and that, like with secret service archives whose documents can now be declassified, it can now be revealed how they were done. I decided to pose for the cover of the book with my face painted with guerrilla camouflage in allusion to the discretion required in order to reach the goal. The book will be useful for universities and for those who want to embark on this same path of communication. This is why it's being issued in two editions: besides the Spanish version, it's also appearing in English, aimed not just at English-speaking countries, but also at the professional, academic and international university publics.

What would you highlight about the book?

- Its principal significance is in the sum of its unique experiences, the entirety of the 27 cases chosen from a long list. They are enormously complex and painstaking examples, especially because they required an incredible level of detail in order for their messages to reach their objectives without straying off course. I'm not only used to being at the origin of the idea, but part of its execution and dissemination… because that way I can ensure that the thrust of the impulse is maintained from the beginning to the final impact, and that the essence of the message remains intact. Nonetheless, along with the most historical campaigns among the examples I present, what I'm most happy with is the introduction, in which I recount the link between my journalism career and my posterior work with guerrilla marketing. I tell how before buying the Berlin Wall segments I crossed the Wall, and before acquiring the Scud missile in Russia I heard their roar in the night above Basra, in Iraq during the war with Iran. So I've included the introduction on the website GuerrillaBook.com, so people can read the background before buying the book.

REPERCUSSIONS

PRINTED MEDIA

- Emarat Al Youm | 10/07/2015

- Woman | 01/04/2015

- El Diario Montañés | 02/03/2015

- La Verdad | 02/03/2015

- El Norte de Castilla | 02/03/2015

- Sur | 02/03/2015

- Emarat Al Youm | 01/03/2015

- Hoy Zalamea | 01/01/2015

- El Mundo ORBYT | 01/01/2015

- Viajar | 01/01/2015

- El Periódico de Catalunya | 14/12/2014

- La Razón | 13/12/2014

- Marketing en la crisis | 01/03/2015

- ElBlogFeroz.com | 10/11/2014

- Emarat Al Youm | 10/07/2015

- MK | 01/07/2015

- Emarat Al Youm | 01/03/2015

- Diario de Navarra | 01/03/2015

- El Diario Vasco | 01/03/2015

- Ideal | 01/03/2015

- El Diario Montañés | 01/03/2015

- Hoy | 01/03/2015

- El Correo | 01/03/2015

- La Verdad | 01/03/2015

- El Norte de Castilla | 01/03/2015

- La Rioja | 01/03/2015

- Sur | 01/03/2015

- Las Provincias | 01/03/2015

- Ibercampus.es | 19/01/2015

- El Imparcial | 17/01/2015

- Viajar - web | 01/01/2015

- Qué Crack | 01/01/2015

- Rutas pangea.com | 01/01/2015

- InSpain.org | 01/01/2015

- Infoperiodistas.info | 15/12/2014

- La Razón.es | 12/12/2014

- El Pulso.es | 12/12/2014

- EntornoInteligente.com | 12/12/2014

- Intereconomía TV - El Telediario | 03/12/2014

- Negocios.com | 27/11/2014

- Inmediatika.es | 15/11/2014

- LasIniciativas.com | 14/11/2014

- ElMundo.es | 10/11/2014

- La Provincia | 10/11/2014

- La Provincia | 10/11/2014

- La Provincia | 10/11/2014

- Tweet CNN en Español | 10/11/2014

- La Provincia | 09/11/2014

- La Provincia | 09/11/2014

- LaInformacion.com | 06/11/2014

- Europa Press | 04/11/2014

- Efe | 04/11/2014

- EntretantoMagazine.com | 04/11/2014

- ElDia.es | 04/11/2014

- LaVanguardia.com | 04/11/2014

- Caracol.com.co | 04/11/2014

- LaVozLibre.com | 01/11/2014

- ReasonWhy.com | 01/01/2014

DIGITAL MEDIA

TELEVISION